INDEX

- About Intra-abdominal Pressure Monitoring and Intra-abdominal Hypertension or Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Procedure for Measuring Intra-Abdominal Pressure (IAP)

- Documentation of Intra-Abdominal Pressures in One Chart

- Printable Checklist: Procedure for measuring Intra-Abdominal Hypertension (IAC) or Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Patients at risk for Intra-Abdominal Hypertension or Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Interventions for Intra-Abdominal Hypertension or Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Link to 2013 Decision-Tree (Kirkpatrick)

What is Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome??

It is the measurement of the pressure inside the abdominal compartment.

Normal Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP) is 0 - 5 mmHg; 5-7 mmHg during critical illness.

Intra-abdominal Hypertension (IAH) is defined by pressures > 12 mmHg (may be sufficient to restrict perfusion to the organs of the gut)

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) is defined as sustained pressures > 20 mmHg with evidence of organ dysfunction. General surgery notification should be considered and lactate monitored closely.

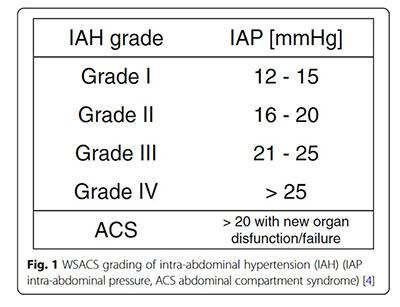

IAH is graded as follows:

Abdominal compliance refers to the ability of the abdominal compartment to accommodate volume and is influenced by the elasticity of the abdominal wall and diaphragm. It should is expressed as the change in intra-abdominal volume per change in IAP

Abdominal Perfusion Pressure (APP) should be > 60 mmHg and is defined as:

APP = MAP – IAP

APP is dependent upon an adequate MAP and low IAP

Primary IAH or ACS is the result of abdominopelvic injury or disease and often requires surgical or interventional radiology treatment

Secondary IAH or ACS is the result of conditions that originate outside the abdominopelvic region (e.g., systemic inflammation)

Pressure may rise rapidly with active bleeding. Edema (which occurs with any ischemic insult) will generally result in a later rise in the pressure (27 hours or more post insult)

Polycompartment syndrome is a condition where two or more anatomical compartments have elevated pressures

An open abdomen is a method for surgical decompression that requires a temporary abdominal wound closure because the skin and fascia have been left open.

Lateralization of the abdominal wall is a phenomenon where the musculature and fascia of the abdominal wall moves laterally away from the midline

How is Intra-abdominal Compartment Pressure measured?

It can be measured directly by inserting a catheter into the abdominal compartment, or indirectly, by monitoring the pressure in the bladder, stomach or other cavities. The simplest and most frequently used method is to measure bladder pressure from an indwelling Foley catheter.

Why is it done?

All patients who are edematous, critically ill or who have abdominal distension for any reason are at risk. ARDS, intraabdominal disorders and inflammatory states are important risk factors.

The pressure inside the abdominal compartment can increase following trauma, as a result of the accumulation of blood, fluid or edema. Non-traumatic bowel ischemia/infarction or gastrointestinal hemorrhage can also lead to increased pressure in the abdominal compartment as ischemic cells swell or fluids collect. Coagulopathies with abdominal bleeding, cirrhosis, or profound hypothermia are other potential causes. Once the pressure in the abdominal compartment overcomes the pressure inside the capillaries that are responsible for perfusing the organs, ischemia and infarction of organs can occur.

Abdominal compartment pressure monitoring is done to help recognize life threatening elevations in pressure before ischemia or infarction of the abdominal organs occurs. When a patient exhibits a distended and taut abdomen, the measurement of abdominal compartment pressure can provide direction regarding the need for decompressive surgery.

Procedure for Intra-abdominal Compartment Pressure?

Abdominal compartment syndrome pressure can be measured very quickly, by hooking a pressure monitoring system up to the Luer-lock connection of the drainage collecting tubing. Measurement via the drainage tubing sampling port (versus catheter) allows measurements from any catheter that is connected to continuous drainage.

The pressure monitoring circuit can be left connected to avoid opening of a closed circuit. Intermittent connection is often preferred to facilitate patient care/turning.

If the circuit is intermittently connected for pressure monitoring, it is important to ensure aseptic technique is maintained. The sampling port should be covered with an alcohol-based cap (like IV connections) and the ends of any tubing/syringes are kept sterile.

Prior to measuring pressure, the bladder should be empty. A volume of 25 ml of saline should be instilled into the empty bladder to allow pressure to facilitate pressure wave transmission while maintaining a constant bladder volume with each measurement.

All pressures should be taken with the patient lying supine, head flat and transducer level confirmed. Each measurement should be taken at end expiration.

PROCEDURE: ABDOMINAL COMPARTMENT PRESSURE MONITORING VIA BLADDER CATHETER

| ||

Key Points for Accurate Measurement

- Patients do not require deep sedation, analgesia or neuromuscular blockade for initial screening. If pressure is elevated, sedation and or neuromuscular blockade may be considered to rule-out false positive due to abdominal wall resistance.

- Position the head of bed flat with patient supine to relax abdominal wall. Place hand over abdomen to assess for muscle relaxation.

- Level and zero transducer to mid-axillary line with patient supine and bed flat. Be aware that intra-abdominal pressure may increase after head of bed is elevated due to increased abdominal wall resistance, particularly in patients with elevated pressures (ie. abdominal pressure measured flat may underestimate the pressure after HOB elevation),

- Scrub the hub of the sampling port on the catheter drainage tubing and allow to dry one minute. Connect the pressure tubing to the sampling port as shown in Figure 1.

- Ensure bladder is empty, then clamp the drainage tubing with a Kelly clamp as shown in Figure 1.

- Connect the syringe to the Luer-lock connection on the extension connection of the pressure tubing as shown in Figure 1. c

- Turn the stopcock open to the saline and fill the syringe with 25 ml of 0.9% normal saline. Turn the stopcock open to the patient catheter and instill the 25 ml of saline. Turn the stopcock off to the syringe (open to patient and transducer). Volumes higher than 25 ml can overestimate the pressure, while lower volumes can prevent waveform transmission, and use of a consistent volume reduces variance due to bladder volume.

- The abdominal blood flow should produce fluctuations in the waveform with the heart beat and show pressure variations with breathing. Flush the pressure system if waveform variation cannot be detected.

- Wait 60 seconds after instilling saline to give bladder muscle time to relax.

- Measure pressure at end-expiration. Print the waveform and place in the clinical record. Measure and document the end-expiratory pressure in the electronic record Q6H if pressure remains less than or equal to 12 mmHg and Q4H if pressure is greater than 12 mmHg. Report a pressure greater than 12 mmHg to the provider.

- Disconnect pressure tubing. Place an antimicrobial female end-cap on the end of the pressure tubing and an antimicrobial male Luer-lock cap on the sampling port of the urinary drainage tubing.

- If intra-abdominal pressure is greater than 12 mmHg, review the "Management of Intra-Abdominal Hypertension" with provider and initiate the interventions that are appropriate for this patient. Implement interventions that do not require an order immediately.

- Monitor for signs of organ dysfunction due to increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., rising lactate, decreased urine output, impaired ventilation, mental status changes, hypotension, decreased venous oxygen saturation).

Documentation

Document in the Electronic Health Record as follows:

In IView, choose Vital Signs and Customize View.

Risk Factors for Intra-Abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Diminished abdominal wall compliance

Abdominal surgery

Major trauma

Major burns

Prone positioning

Increased intra-luminal contents

Gastroparesis/gastric distention

Ileus

Colonic pseudo-obstruction

Volvulus

Increased intra-abdominal contents

Acute pancreatitis

Distended abdomen

Hemoperitoneum/pneumoperitoneum

Intra-peritoneal fluid collections

Intra-abdominal infection/abscess

Intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal tumors

Laparoscopy with excessive insufflation pressures

Liver dysfunction/cirrhosis with ascites

Peritoneal dialysis

Capillary leak/fluid resuscitation

Acidosis

Damage control laparotomy

Hypothermia

Increased APACHE-II or SOFA score

Massive fluid resuscitation or positive fluid balance

Polytransfusion

Others/miscellaneous

Age

Bacteremia

Coagulopathy

Increased head of bed angle

Massive incisional hernia repair

Mechanical ventilation

Obesity or increased body mass index

PEEP

Peritonitis

Pneumonia

Sepsis

Shock or hypotension

Management of Intra-abdominal Hypertension (IAH) and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS)

Link to 2013 Decision-Tree (Kirkpatrick)

Reduce abdominal wall tension:

- Use sedatives and narcotics to reduce abdominal muscle tone

- Remove any restrictive dressings or binders from abdominal wall

- Add neuromuscular blockers (if sedation/analgesia alone inadequate)

- Reverse Trendelenburg may reduce IAP (especially in obese or pregnant patients)

Position patient to lower intra-abdominal pressures:

- Two studies suggested that IAP measured when patient is supine may underestimate the IAP after HOB elevation. HOB elevation should be modified or avoided in ACS.

- Keep HOB < 20 degrees (lower if needed to manage ACS). HOB elevation and/or hip flexing positions may increase IAP.

- If HOB elevation is required (e.g., concurrent intracranial hypertension), use reverse Trendelenburg and avoid hip flexion

- Avoid prone positioning (3 studies report increased pressures)

Reduce intra-luminal gastrointestinal contents:

- Insert NG and rectal drainage tubes

- Promote bowel elimination through use of laxatives and/or enemas unless contraindicated

- Initiate gastro-colonic prokinetic agents if appropriate (e.g., metoclopramide or neostigmine for ileus). Caution: neostigmine can cause asystole, monitor carefully during administration and have atropine/epinephrine/pacing available prior to administration in case of adverse event

- Minimize enteral feeding volume and/or discontinue enteral feeding

- Consider colonoscopic decompression

Evacuation of intra-abdominal contents:

- If IAH or ACS is identified, intra-abdominal causes should be ruled-out quickly using ultrasound and CT if indicated

- Percutaneous drainage of ascites or abscess may be considered

- Consider surgical decompression for intra-abdominal perforation (or overt surgical indication) or for ACS with worsening organ failure

- Use wound VAC post decompression to promote removal of intra-abdominal fluid and/or possibly proinflammatory cytokines

Optimize fluid balance and maintain an adequate abdominal perfusion pressure:

- Dehydration and inadequate intravascular fluid volume may decrease abdominal perfusion pressure and increase risk for ischemia, but a positive fluid balance may increase IAP as a result of third space loss to the abdomen

- Avoid excessive fluid administration and strive for neutral or negative balance

- Currently, the evidence is not clear regarding the use of diuretics during IAH/ACS or albumin/hypertonic solutions. Consider on an individual patient basis

- Vasopressors may be required to maintain adequate abdominal perfusion pressure

Maintain an adequate abdominal perfusion pressure and use goal directed resuscitation:

- Individualize treatment based on clinical end-points of organ function

- Individualize and optimize hemodynamics and abdominal perfusion pressure (e.g., Point of Care Ultrasound, IAP trends, optimize oxygen transport)

- Like the management of cerebral perfusion pressure, abdominal perfusion pressure is dependent upon an adequate driving pressure (MAP) and low IAP. Individualized treatment as required to maintain an adequate MAP and reduction in elevated IAP.

Classification of open abdomen

Modified classification scheme for the complexity of the open abdomen (Bjorck, 2016)

Open abdomen is classified according to whether there is “fixed”, if there is contamination and the degree of contamination.

Fixation refers to the mechanical properties of the abdomen. A “fixed” abdomen has adhesions between the abdominal wall and contents that impair elasticity and compliance.

1 No Fixation

1A: No fixation

1B: Clean, no fixation

1C: Enteric leak, no fixation2 Developing fixation

2A: Clean, developing fixation

2B: Contaminated, developing fixation

2C: Enteric leak, developing fixation3 Frozen abdomen

3A: Clean, frozen abdomen

3B: Contaminated, frozen abdomen4 Established enteroatmospheric fistula, frozen abdomen

Bjorck (2016)

What findings may indicate organ dysfunction?

Patients with abdominal compartment syndrome should be monitored for the following:

- Oliguria due to renal ischemia

- Increased airway resistance/decreased lung compliance, reduced tidal volumes/hypoxemia/hypercarbia

- Hypotension and decreased cardiac output

- Gastrointestinal bleeding/blood diarrhea/rising lactate due to ischemia of the bowel

- Increased creatinine, bilirubin, LFTs

- Impaired distal extremity circulation secondary to pressure on the aorta

- Increased intracranial pressure

The most common findings of abdominal compartment syndrome are renal and cardiopulmonary complications. In head injury, increased abdominal compartment pressure can increase ICP. Monitoring for abdominal compartment syndrome in patients who are at risk for intracranial and intra-abdominal hypertension is important.

Brenda Morgan

Clinical Educator, CCTC

September 1999

Revised: Revised January 19, 2022, Reviewed January 16, 2025

References:

Bjorck, M., et al. (2016). Amended classification of the open abdomen. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. Mar;105(1):5-10.

Bloomfield, G., Saggi, B., Blocher, C, & Sugerman, H. (1999). Physiologic effects of externally applied continuous negative abdominal pressure for intra-abdominal hypertension. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care. Jun; 46(6): 1014-6.

Cheatham, M. et al. (2007). Results from the international conference on experts on intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. II Recommendation. Intensive Care Medicine. 33:961-962.

Cheatham, M., et al., (2007). The impact of body position on intra-abdominal pressure

measurement: A multicenter analysis. Crit Care Medicine, 37(7), 2187-90.

Coccolini F, Roberts D, Ansaloni L, Ivatury R, Gamberini E, Kluger Y, Moore EE, Coimbra R, Kirkpatrick AW, Pereira BM, Montori G, Ceresoli M, Abu-Zidan FM, Sartelli M, Velmahos G, Fraga GP, Leppaniemi A, Tolonen M, Galante J, Razek T, Maier R, Bala M, Sakakushev B, Khokha V, Malbrain M, Agnoletti V, Peitzman A, Demetrashvili Z, Sugrue M, Di Saverio S, Martzi I, Soreide K, Biffl W, Ferrada P, Parry N, Montravers P, Melotti RM, Salvetti F, Valetti TM, Scalea T, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Kashuk JL, Larrea M, Hernandez JAM, Lin HF, Chirica M, Arvieux C, Bing C, Horer T, De Simone B, Masiakos P, Reva V, DeAngelis N, Kike K, Balogh ZJ, Fugazzola P, Tomasoni M, Latifi R, Naidoo N, Weber D, Handolin L, Inaba K, Hecker A, Kuo-Ching Y, Ordoñez CA, Rizoli S, Gomes CA, De Moya M, Wani I, Mefire AC, Boffard K, Napolitano L, Catena F. The open abdomen in trauma and non-trauma patients: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2018 Feb 2;13:7. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0167-4. PMID: 29434652; PMCID: PMC5797335.

De Laet, I.E., Malbrain, M.L.N.G. & De Waele, J.J. A Clinician’s Guide to Management of Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome in Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care 24, 97 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2782-1

Diebel, L., Dulchavsky & S., Brown, W. (1997). Splanchnic ischemia and bacterial translocation in the abdominal compartment syndrome. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care. Nov; 43(5): 852-5.

DynaMed. Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. EBSCO Information Services. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/abdominal-compartment-syndrome

Ivatury, R., et al. (1998). Intra-abdominal hypertension after life-threatening penetrating abdominal trauma: prophylaxis, incidence, and clinical relevance to gastric mucosal pH and abdominal compartment syndrome. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care. Jun; 44(6): 1016-23.

Jang H, Lee N, Jeong E, Park Y, Jo Y, Kim J, Kim D. Abdominal compartment syndrome in critically ill patients. Acute Crit Care. 2023;38(4):399-408. doi: 10.4266/acc.2023.01263

Kirkpatrick, A. et al. (2013). Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 39:1190-1206.

Malbrain, M. et al. (2006) Results from the international conference of experts on intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. Intensive Care Med, 32:1722–1732

DOI 10.1007/s00134-006-0349-5

Milanesi, R and Caregnato, RC. (2016). Intra-abdominal pressure: An integrated review. Einstein. 14(3): 423-30.

Nasa P, Wise RD, Smit M, Acosta S, D'Amours S, Beaubien-Souligny W, Bodnar Z, Coccolini F, Dangayach NS, Dabrowski W, Duchesne J, Ejike JC, Augustin G, De Keulenaer B, Kirkpatrick AW, Khanna AK, Kimball E, Koratala A, Lee RK, Leppaniemi A, Lerma EV, Marmolejo V, Meraz-Munoz A, Myatra SN, Niven D, Olvera C, Ordoñez C, Petro C, Pereira BM, Ronco C, Regli A, Roberts DJ, Rola P, Rosen M, Shrestha GS, Sugrue M, Velez JCQ, Wald R, De Waele J, Reintam Blaser A, Malbrain MLNG. International cross-sectional survey on current and updated definitions of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. World J Emerg Surg. 2024 Nov 29;19(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13017-024-00564-5. PMID: 39609850; PMCID: PMC11605967.

Offner, P. & Burch, J. (1998). Abdominal compartment syndrome, part 1: presentation and workup: cardiopulmonary and renal findings are among the most prominent signs. Journal of Critical Illness. Oct; 13(10): 634-8.

Offner, P. & Burch, J. (1998). Abdominal compartment syndrome, part 2: management guidelines: which patients will require abdominal decompression? Journal of Critical Illness. Oct 13(10): 639-42.

Williams, M. & Simms, H. (1997). Abdominal compartment syndrome: case reports and implications for management in critically ill patients. American Surgeon. Jun; 63(6): 555-8.